The History of Alzheimer's

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible brain disorder that steadily progresses and destroys a person’s cognitive skills and overall functioning.

Alzheimer’s disease is not a regular part of the aging process. Memory impairments are often one of the first signs of Alzheimer’s disease, along with challenged reasoning and judgment, confusion, disorientation, and difficulty with word-finding.

In addition, people with Alzheimer’s disease experience depression, behavioral changes, impaired vision, spatial difficulties, and other problems.[i]

Although it is unclear what causes Alzheimer’s-related dementia in most people, research has shown that the contributing factors most likely include a mix of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle causes.

While in people with early-onset Alzheimer’s, the disease may be caused by a change in their genes, in late-onset cases, the condition is often caused by a series of brain changes that happen over their lifespan.[ii]

But how was Alzheimer’s disease discovered?

The Discovery of Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is named after the doctor Alois Alzheimer, who discovered it at the beginning of the 20th century.

Dr. Alzheimer was a young psychiatrist in his late 30s when he met Auguste Deter in 1901. She was a patient admitted to the Community Hospital for Mental and Epileptic Patients in Frankfurt, Germany.

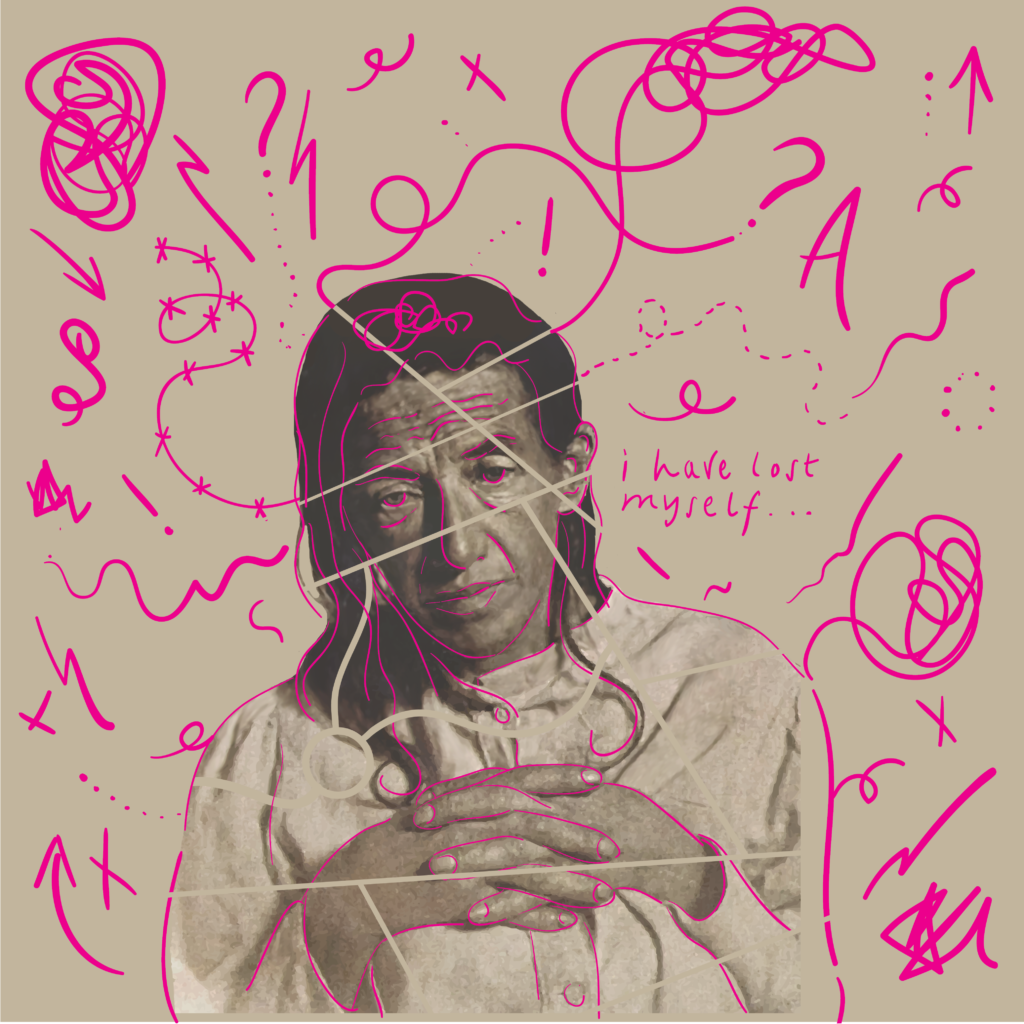

Dr. Alzheimer had worked on understanding the connection between brain disease and mental illness when he met Auguste Deter. At 51, she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital because of her increasing memory problems. Cognitive decline was accompanied by progressive sleep problems, confusion, trouble speaking, and paranoid and aggressive behavior.

She remained in the hospital until her death in 1906. Dr. Alzheimer followed Auguste Deter for five years at the hospital, meticulously documenting the progression of her unusual disease.

When examining Deter’s brain after her death, Dr. Alzheimer noticed strange changes.

He found clumps and tangled bundles of fibers in the brain tissue, typically seen in what was then known as “senile dementia.” He named the condition “presenile dementia” as his patient was not an elderly woman when it started.

The Limited Enthusiasm Over Dr. Alzheimer's Findings

At the 37th Meeting of South-West German Psychiatrists in Tübingen on 3 November 1906, Dr. Alois Alzheimer reported “a peculiar severe disease process of the cerebral cortex,” noting these unusual plaques and tangled fiber bundles in the patient’s brain histology.[i]

The clumps Dr. Alzheimer identified are today known as amyloid plaques – clumps of proteins in the spaces between nerve cells that don’t fold correctly. The amyloid plaques first start to form in the parts of the brain responsible for memory and other cognitive functions. Alzheimer’s disease is thought to be caused by these abnormally configured proteins.[ii]

The tangled bundles of fibers (now called neurofibrillary or tau tangles) that Dr. Alzheimer discovered in the brain tissue are today known to be abnormal accumulations of a tau protein that builds up inside neurons.[iii]

Plaques and tangles in the brain and the loss of connections between brain cells are still thought to be the most critical signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

During the Tübingen meeting, though, the session’s chair, the famous psychiatrist Alfred Hoche, didn’t care about Alzheimer’s presentation. Instead, he asked the following speakers to carry on talking about psychoanalytical topics.

Furthermore, just two paragraphs were allocated to Alzheimer’s lecture in the official records of the Tübingen meeting, but the psychoanalytical lectures that followed Alzheimer’s presentation were widely commented on.

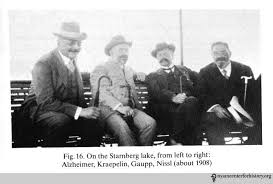

Emil Kraepelin, a colleague of Alzheimer’s, wrote about the case of Auguste Deter in the 1910 edition of his Handbook of Psychiatry. He named this type of dementia after his young research assistant and colleague, Alzheimer.

Dr. Alois Alzheimer’s original notes on Augusta Deter’s case were lost for more than seventy years until they were recovered in the archives of the Goethe University Hospital in Frankfurt by Prof. Dr. Konrad Maurer.[iv]

Who was Dr. Alois Alzheimer?

Alois Alzheimer (14 June 1864 – 19 December 1915) was a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist.

He studied medicine at the University of Berlin, the University of Tübingen, and the University of Würzburg. Alzheimer graduated from the University of Würzburg as a Doctor of Medicine in 1887

The following year, he accepted a position at the Institute for Mental and Epileptic Patients in Frankfurt, Germany. He collaborated with Franz Nissl, a noted neuropathologist, in studying nervous system disease, particularly the normal and abnormal anatomy of the cerebral cortex. Research into the organic causes of mental illness, obtained after an autopsy, was a critical component of their work.

Dr. Alzheimer was astounded by the institute’s inadequate sanitary measures, living circumstances, and the patients’ restricted care. Together with Nissl and Emil Sioli, Alzheimer transformed the institute into a professional mental clinic and a compassionate center. They utilized a non-restrictive patient treatment characterized by physician-patient communication and bath treatment.

While working in Frankfurt hospital, young Alzheimer met Emil Kraepelin, one of the most prominent German psychiatrists of that period. Kraepelin became Alzheimer’s mentor and colleague as they worked closely together over the next few years.

While working in Frankfurt, Alzheimer met and married his wife, Cecilia Geisenheimer (née Wallerstein).

However, his wife died in 1901, just a few months after the birth of their third child, at the age of 41. Following his wife’s death, Alzheimer worked harder in the hospital to cope with his loss. Then, in November 1901, he started evaluating a patient named Auguste D., who had just been admitted to the hospital. He didn’t know at the time that his work with this patient would lead to a discovery that would make him famous all over the world.

In 1903, Alzheimer joined Kraepelin at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital in Munich.

In 1912, he moved from Munich to Silesian Friedrich Wilhelm University in Breslau. He became a professor of psychiatry and head of the Neurologic and Psychiatric Institute.

Unfortunately, Aloise Alzheimer’s health deteriorated soon after gaining the chair of psychiatry in Breslau. He passed away three years later and long before his name became a synonym for the most common type of dementia.[i]

References

[1]https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447

[1]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181715/

[1] https://www.news-medical.net/health/What-are-Amyloid-Plaques.aspx#:~:text=Amyloid%20plaques%20are%20aggregates%20of,memory%20and%20other%20cognitive%20functions.#[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/neurofibrillary-tangle

Thank you for nice information

I love it when folks come together and share ideas. Great blog, continue the good work!

I quite like reading an article that will make people think.

Also, thank you for permitting me to comment!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Great article! You covered the topic thoroughly and provided valuable insights.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve really enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!